In parts of the United States, making home-brew moonshine is considered a tradition; as much a part of the country’s culture as anything else.

Turn back the clock a few decades and moonshine manufacture wasn’t always an art or a tradition. For many, it was a means of survival, with men brewing moonshine to ensure that their families would have food on the table and a roof over their heads.

Starting in the Prohibition era of the 1920s, big city gangsters like Al Capone paid small-town brewers to provide them with cut-price, illegal alcohol to distribute among speakeasies.

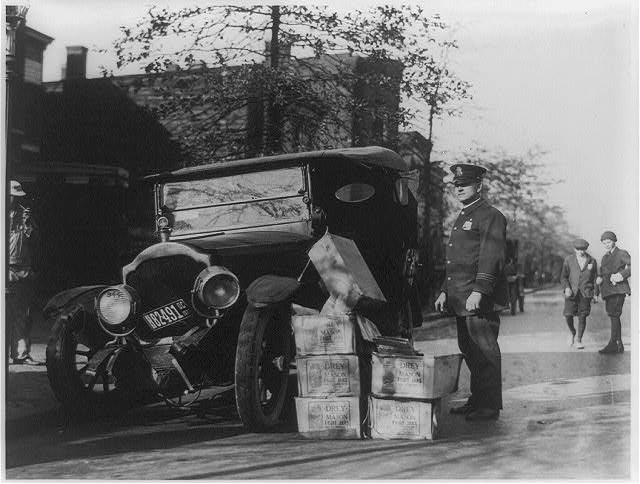

Law enforcement naturally took a dim view of this enterprise, forcing still operators to work after dark, hence the term “moonshine”. As with any business, manufacturing the product was only half the challenge, and the job of getting it from stills to customers fell to the bootleggers.

It was the bootleggers’ job to transport the alcohol across the Canadian border or across “dry” states. Having to distribute their illicit products under the radar quickly, moonshiners were forced to develop and modify their cars in order to avoid getting caught by lawmen.

“You had to have fast cars to haul your whiskey to the people and to get away from the revenuers, the Alcoholic Beverage Control commission and the federal officers,” says Junior Johnson, one of the greatest legends in NASCAR racing and a former North Carolina bootlegger.

Although Prohibition was repealed in 1933, the taste for illegal moonshine endured until the 1960s, and a number of drivers continued “runnin’ shine” while evading the tax men who were attempting to scupper their operations.

The cars continued to improve alongside it, and by the late 1940s had moved into the mainstream consciousness, being run for pride and profit and giving birth to fledgling stock car racing events like NASCAR.

“If it hadn't been for whiskey, NASCAR wouldn't have been formed. That's a fact,” adds Johnson, who was jailed a year after he began his racing career for running an illegal whiskey still, a crime that was pardoned 30 years later by President Ronald Reagan.

Key to the moonshiners’ plans to evade detection was using cars which looked every day on the surface, but which had been modified by their drivers for extra power, better handling and increased cargo capacity.

According to the late Benny Parsons, another former NASCAR driver and moonshiner, some of the methods used to hop the cars up was to add more carburettors to allow the car to burn more fuel, while new intake manifolds were added to increase airflow to the engine.

If runners needed a lot of extra power, they commonly added early versions of turbochargers and superchargers, while increasing engine displacement by over-boring the cylinders was also common.

Some claimed that they were able to make over 500 horsepower with their modifications, but speed wasn’t necessarily everything. The loads that each car carried was typically extremely heavy, and the high speeds at which they were driven put further stress on the vehicles.

In order to handle heavier loads at higher speeds, moonshiners would also get creative with the suspension, adding more leaf springs to stiffen it up and help with load weight distribution.

Other modifications included an array of Bond-style gadgetry like hidden tanks under the car’s floorboards which could be filled with moonshine, flipping licence plates and toggle switches that would shut off the tail lights so the cars couldn’t be followed.

Along with the modifications, the drivers themselves were notorious among lawmen for their wild on-road antics, with a raft of daring manoeuvres developed to evade tax agents, including 180-degree turns on a moment’s notice.

Junior Johnson pioneered his own variation of the move; not only would he spin around 180 degrees, he would also charge head-on at the pursuing agent’s car to force them off the road.

Joe Carter, a former agent, said: “Junior had a reputation for being a guy who had a hotrod with a one-brake wheel. He could go down the road and hit that brake and turn around in one lane of a highway and head back the other way at great speed.

“Those kids knew every damn curve in the county and how much speed they could take it at in certain weather conditions.”

Still, rudimentary upgrades and creative driving skills could only take the moonshiners so far. For every advancement they made, they could be sure that the long arm of the law would be only two steps behind.

Benny Parsons said: “Soon they had to go to other engines, they would swap in the Cadillac engines to get all the horsepower they could, or even swap in old ambulance engines for long and fast hauls.”

The real breakthrough for the ‘shiners was the introduction of the Ford flathead V8, which first debuted in 1933 on Ford’s Model B.

Incredibly simple by today’s standards, at the time the flathead was unsurpassed by any other engine for its ability to provide go-fast power on the cheap. Relatively common and easy to come by, the V8 enjoyed a symbiotic and meteoric rise alongside the advent of moonshine running, with drivers tuning them to get every last horse pulling.

In fact, Junior Johnson’s favoured car during his running days was a 1940 Ford Coupe, outfitted with a flathead V8 which he supercharged himself. “We didn’t back down in doing whatever we could do to make them cars faster,” he said.

“You didn’t have no top end on ‘em with a supercharger. That thing would just keep gettin’ up. It had the power to take it where the road was so narrow, you couldn’t imagine how fast that thing was a-runnin’.”

Incidentally, the hooch huffers weren’t the only ones operating outside of the law who had a liking for the V8, either. In 1934, a year after the Model B cabriolet was introduced, Ford received a letter from bank robber Clyde Barrow, of Bonnie and Clyde infamy.

Barrow personally wrote to Ford, praising the V8 as a “dandy car” and added: “For sustained speed and freedom from trouble the Ford has got every other car skinned.”

By the 1950s and 60s, moonshine had lost most of its appeal, largely thanks to politicians in formerly “dry” areas realising that more money could be made by selling spirits legally. As county after county legalised alcohol, bootleggers found themselves without a trade, but the taste for modifying cars for performance lived on.

As American as baseball and apple pie, highly-customised, high-performance cars had entered the national consciousness as a way to reflect the innovation, resourcefulness and rebellious qualities that the US associated as its national spirit.

In the twilight years of moonshining, Southern California began to become a centre for custom car competitions, with amateur racers testing the tried-and-true methods pioneered by the bootleggers to set speed records on dry lakebeds.

Many ex-moonshiners banded together and began racing for the newly-formed National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, which was formed by promoter and reputed bootlegger Bill France in 1947.

In parallel, the nascent hot-rodding community founded the National Hot Rod Association in 1951. Later, it found an ally in Detroit as Motor City started to introduce the first muscle cars, themselves following the moonshiners’ ethos of taking a relatively everyday car and slamming a massive V8 engine in it.

Suddenly, art, hairstyles and fashions drawn from early hot-rodders started to become known as “Kustom Kulture”, with designer Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s Rat Fink character becoming popularised on everything from decal stickers to T-shirts.

Oil embargoes in the 1970s slowed progress temporarily, but skip forward to the modern day and hot-rodding, modifying and uprating cars and engines is just as prevalent as ever.

Thanks in part to film franchises like The Fast and the Furious, video games like Need for Speed and the SEMA aftermarket parts convention, taking a stock vehicle and modifying it to better suit your needs has never been as popular or as accessible for the everyday driver.

Car customisation can nowadays be a full-time occupation, with many businesses dedicated to creating custom dream machines that employ the latest and greatest automotive designs and technologies.

Drivers mightn’t use them to escape federal agents any more, and Ford hasn’t sold a new flathead V8 for 62 years, but while the tools might have changed, today’s car builders carry the same passion, ingenuity and daring as the original moonshine hot-rodders of 80 years ago.