Spare a thought for the humble, hapless crash test dummy, the unsung hero of the automotive industry. These unassuming rubber humanoids have saved potentially hundreds of thousands of lives over the years and ask for no thanks in return. Indeed, not all heroes wear capes.

Of course, most heroes don’t save lives by being repeatedly and violently smashed into a wall either, but that’s beside the point. But with automotive technology coming on leaps and bounds, cars are now safer than ever before so where does the future lie for crash test dummies?

First of all, let’s take a look at their history. Throughout the hundred-plus year history of the automobile, safety has always been a serious concern for car makers; after all, who wants to buy a car they’re likely to end up dying in?

The first recorded victim of a car accident was Mary Ward, who was struck by a steam-powered car on August 31st 1869, a full 17 years before Karl Benz would invent the first petrol-powered automobile.

History of the crash test dummy

From the start, car manufacturers wanted to understand how the human body reacts to crashes, and how better to test that than by crashing cars full of actual people? Somewhat gruesomely, the first crash test dummies in history were actually human cadavers taken from Detroit’s Wayne State University.

Of course there were all sorts of ethical and moral issues about the desecration of people’s corpses, but the researchers argued that their work was significant enough to warrant the use of the cadavers. By the mid-1950s, researchers had taken crashing dead bodies into walls as far as it could go, and needed more options for assessment.

In what seems like a serious step backwards, researchers offered to pay live volunteers to sit in test cars while the manufacturers crashed them, with the first known live crash test dummies being Colonel John Paul Stapp of the US Air Force and university professor Lawrence Patrick.

You’d think that the researchers could have worked out already the fact that crashing living people into walls usually resulted in them ending up as dead people, but the testing went on until the subjects couldn’t withstand their physical injuries any more.

After human trials were phased out, researchers instead decided to use live animals like pigs, apparently because the testers claimed that pigs have a similar internal structure to humans. Naturally, strong opposition from animal rights groups put a swift end to that.

The first true crash test dummy in the way we know them today was named Sierra Sam and built by researcher Samuel W. Alderson in 1949. Sierra Sam was much taller and heavier than the average human and was used to test aircraft ejector seats, but Alderson later collaborated with General Motors and Ford on a more realistic version, the VIP-50.

Since then, dummies have undergone a number of updates and refinements to make them increasingly realistic, and towards the end of the 1970s General Motors introduced the Hybrid III dummy, which remains the most widespread crash test dummy used to this day.

While earlier models were almost exclusively built like adult males, the Hybrid III was joined by an entire family, including female models and three different child dummies to represent a ten-year old, a six-year old and a three-year old toddler.

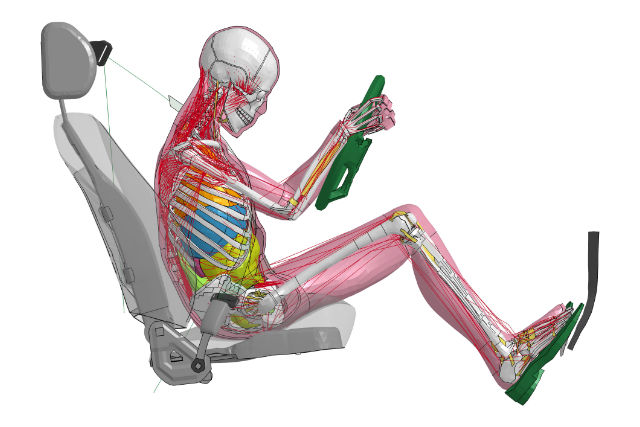

As technology has become further and further advanced, modern test dummies are now fitted with sensors that can record with incredible accuracy metrics like velocity of impact, crushing force, bending and folding forces, plus deceleration rates.

Things have certainly come a long way since the days of crashing corpses into walls and examining the bloody mess left behind, but now with an increasing focus on computer systems are dummies like Sierra Sam and the Hybrid III family in danger of being left behind too?

In fairness, it makes a lot of sense. Safety is even more of a concern these days than it was in previous decades, and how else can car manufacturers be absolutely sure that their cars will give passengers the right protection?

No matter how many sensors a dummy has, it still can’t simulate the complex nature of the human body or the way that people move and react in dangerous situations. Computer programs, on the other hand, can.

The first crash test dummy computer model was developed in 1996 by First Technology Safety Systems, but four years later Toyota would launch the first version of its THUMS (Total Human Model for Safety) program, which has gone on to be remarkably successful.

The THUMS system builds on a basic virtual framework of the human body structure, but also adds on layers including face and bone detail and even a precise model of the brain. By the time THUMS was in its fourth generation, it could even accurately assess how internal organs are affected by crashes.

By 2011, THUMS had extended its capabilities to account for six different body types, while last year it was able to demonstrate the influence of people realising there’s about to be an impact. Humans tend to instinctively brace themselves, whereas regular dummies are decidedly more passive.

Toyota has claimed that researchers have been able to improve the performance of restraint systems like seatbelts and airbags by predicting how people instinctually move, while THUMS can also simulate changes in posture after an accident has happened.

Despite being pioneered by Toyota, THUMS is now used by a wide variety of different manufacturers and component suppliers, including Audi, Volvo, Renault and even NASA, which is using it in the design process for the spacecraft which will put the first humans on Mars.

So is there still room in the world for a real, physical crash test dummy? Surprisingly, there might be. A team from Loughborough University used the THUMS system to try and simulate what would happen if a pregnant woman was involved in a collision.

However, it wasn’t until the team fitted a container filled with fluid above the pelvis of a crash test dummy that they could accurately find a proper seat belt design for pregnant women. Studies had shown that most pregnant women couldn’t wear a standard belt due to discomfort and THUMS could only work within the parameters of the car’s standard specification.

As a result, while computer generated crash simulations are proving more and more important, it’s still the hardy old crash test dummy which is used to physically test and validate the results of the computer’s programming.

Is there still room for dummies?

Even with the advent of driverless cars, which have been predicted by some experts to reduce the number of on-road collisions by as much as 90 per cent, there’s still always the risk factor that something will go wrong. As a result, there will still always be a necessity to test for all possible outcomes.

While programs like THUMS can do amazing things and predict the results of a myriad of crash situations, steel is steel as bone is bone and so the use of real-world testing rigs and real-sized anthropomorphic testing devices are still crucially important.

So the next time you’re sitting in your big, comfortable car, spare a thought for the likes of Mary Ward, or Colonel John Paul Stapp and the researchers who battled long and hard to improve automotive safety.

Above all, spare a thought for the brave crash test dummies and their families, who have died a million times over so that you, with luck, won’t have to.