Fundamentally, there’s no difference between the car that you drive and a Formula One car. They both probably use internal combustion engines, they have gearboxes, suspensions, wheels, brakes and tyres.

It’s around there that the similarities stop, however. Unlike your vehicle, F1 cars aren’t designed for tooling around on the motorway. Everything about them, from the design to the precise materials used, is made for one thing and one thing only: speed.

The average modern Formula One car can accelerate from 0-62mph in around 1.7 seconds, almost a second quicker than the fastest-accelerating production car. Each can hit top speeds of more than 200mph, and can generate more Gs in the corners than the Space Shuttle generates upon launch.

So what is it about Formula One cars that make them so fast? How can something which shares generally the same design as a road car be capable of generating such incredible speeds?

Engine design

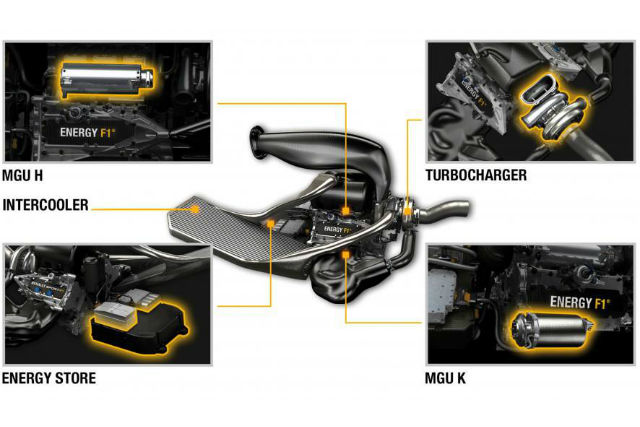

Currently, Formula One cars are powered by 1.6-litre turbocharged V6 engines along with hybrid energy recovery systems, while in the past a variety of different engine types have been used, ranging from 4.5-litre supercharged engines to 3.0-litre V8s.

Even though the size of the engines have dropped dramatically, current Formula One cars can still produce 900bhp or more. To put that in perspective, a Nissan Qashqai with a turbocharged 1.6-litre engine produces just 161bhp.

The reason F1 cars can make so much power from the same size engine is that they use short stroke engines, the same type of motor that’s common in motorcycles.

Bore is the diameter of the cylinder in the engine block, and the stroke is the length of the cylinder. Virtually all road cars have a high stroke to bore ratio, meaning that the shape of the engine cylinders is roughly akin to a toilet roll tube.

By contrast, the cylinders in Formula One cars are shaped more like hockey pucks. The small length but large width allows the car to suck in the same amount of air and fuel as a regular 1.6-litre engine, but the small stroke means the engine’s pistons have a smaller distance to travel, which increases efficiency.

As a result, the cylinder design in conjunction with the advanced metals which makes F1 cars’ engines so durable means that a Formula One car can rev higher and harder. Road cars tend to run out of puff at around 6,000rpm, but in F1 cars regularly rev to upper limits of 19,000rpm which lend them the characteristic whining sound.

Gearboxes

Current Formula One cars use advanced and highly-automated semi-automatic gearboxes, hooked up to paddle shifters mounted on the back of the steering wheel which allows drivers to shift gear with their fingertips.

The design is similar to dual-clutch automatic gearboxes available in passenger cars, but unlike a road car transmission, a Formula One gearbox is automated but not automatic: the driver must engage each gear themselves and use the clutch when starting off to place more emphasis on skill.

Thanks to the fact that they’re manufactured from special low-weight materials like carbon alloys, the gearbox of an F1 car is much lighter than that of a road car, which means less resistance and therefore faster gear changes.

A typical Formula One car can change gear about 50 times faster than a human can blink their eye, with the transmission able to dip the clutch, unhook one gear and engage another in the space of just 0.005 seconds.

Aerodynamics

Formula One cars are as much defined by their aerodynamic look as by their engines. Racing cars are designed to go fast, and any vehicle travelling at high speeds must be able to both reduce air resistance and generate downforce in order to stay stable on the road.

The low, flat and wide design of F1 cars is designed to decrease air resistance, which would otherwise slow the car down as the drivetrain fights against the strain of surrounding air and every single surface of the car is designed to manage airflow to maintain speed and stability.

Every car is covered in a variety of wings, splitters and diffusers, which direct air over and around the car in a controlled manner. They work on fundamentally the same principle as an aeroplane wing, except in reverse, pushing the car down onto the track to maximise tyre traction, particularly when cornering.

More traction in the tyres allows all of the immense power developed by the engine to reach the road underneath, while the least amount of aerodynamic drag allows the cars to attain such high speeds on the straights.

Together, the cars’ aerodynamic addenda is capable of developing 3.5 Gs in downforce, the equivalent of three and a half times the car’s own weight, which means that, in theory at least, a Formula One car could drive upside down at speed.

F1 cars would be able to go even faster if they closed the wheel wells off like in many other racing series, but Formula One has traditionally always been an open-wheel racing series and it looks as though it’s going to stay that way.

Brakes and KERS

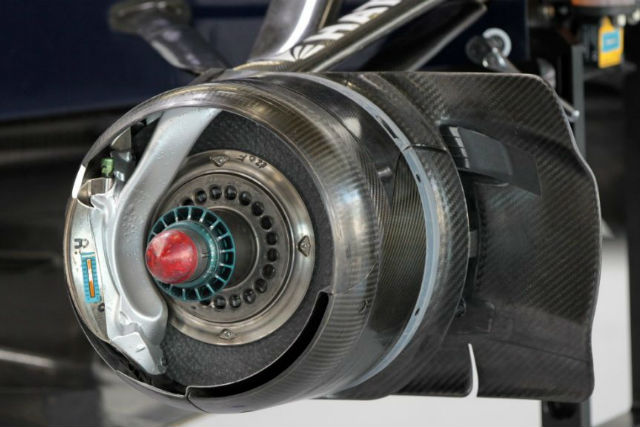

Compared against regular cars, the disc brakes found on F1 cars are more or less identical, with the big difference being that Formula One brakes have to cope with stopping a vehicle travelling at speeds of 200mph or more.

To increase performance and reduce wear and tear, the disks and pads used on F1 cars are made of carbon fibre, which can cope with temperatures that would melt many metals and cause the brakes to weld themselves together.

These efficient brakes also allow the drivers to carry higher speeds into corners to get the best lap times, and are also much lighter than those found in everyday road vehicles.

Kinetic energy that would otherwise escape as heat is instead scooped up by the hybrid kinetic energy recovery system (KERS) found in current F1 cars, and returned to the powertrain for an additional 80bhp power boost that’s available when required.

Tyres

Arguably, it’s the tyres of a Formula One car that are the most important part of the entire vehicle. After all, the tyres are the only part of the car which actually touches the ground and therefore every other major component, from the engine to the suspension, must do its work via the tyres.

If the tyres don’t work well then the car won’t work well, and like every other part of an F1 car, the tyres are highly regulated. For years, teams ran primarily on slick tyres which have no tread pattern and therefore offer the largest possible contact area between rubber and road, but nowadays the rules are different.

To reduce cornering speeds and make the sport more competitive, today’s F1 tyres must be between 12 and 15 inches wide with four continuous grooves running longitudinally around the circumference.

For different weather conditions, tracks and temperatures, teams can choose between soft, medium or hard rubber compounds and dry or wet tyres, which have full tread patterns designed to wick water away from the road surface.

Even the hardest tyres are made of extremely soft rubber compared to road tyres, with the exact composition a jealously guarded secret among manufacturers. The tyres need to heat up in order to achieve their optimum gripping power, meaning that drivers have to warm them up by completing a few laps before the cars are fully race-ready.

The tradeoff of the tyres’ incredible grip is decreased durability. Whereas a standard road tyre for a car can last thousands of miles, Formula One tyres are designed to last for around 125 miles at the absolute maximum.