Last January, luxury jeweller and specialty retailer Tiffany & Co., a brand typically aimed at high-class women and debutantes launched a new ad campaign featuring, for the first time, a gay male couple alongside the traditional heterosexual couples used in its advertising.

The ad, created by New York-based Ogilvy & Mather, went down a storm on social media, with the reception extremely positive and even Miley Cyrus reposting the ad on her Instagram page, declaring Tiffany “badass”.

If such an established, prestigious and historically conservative brand like Tiffany can transcend traditional gender stereotypes, then it begs the question: why are women still critically underrepresented throughout the automotive industry?

It’s a cruel fact but the notion that women have little place in motoring has been thematic throughout the automotive industry’s history, with sexist and patronising attitudes and marketing campaigns stretching back to the earliest days of car advertising.

As far back as the first decade of the 1900s, ad agencies pitched petrol-powered cars to men and early electric cars to women, the idea being that electric cars, which were quieter and slower, were much more appropriate for feminine sensibilities.

Why are women still underrepresented?

Take the Detroit Electric, an early electric car made by the Anderson Electric Car Company, as an example. In its time, the Detroit Electric was reasonably popular and even Thomas Edison owned one, but in its time it was marketed as ideal for a woman who wanted to “preserve her toilet immaculate, her coiffure intact.” Not exactly progressive.

Even as early electric cars fell by the wayside and petrol vehicles took off, the idea that women needed dumbed-down technology persisted. According to Virginia Scharff, author of ‘Taking the Wheel: Women and the Coming of the Motor Age’, when the self-starting car was invented, ads proclaimed that “even a girl can work it”, rather than daring to suggest that men, too, might appreciate not having to laboriously crank their engine into life.

Of course, it would be unfair to tar every car manufacturer and ad man of the era with the same brush, and as the initial decades of the 1900s gave way to the Roaring Twenties, changing perceptions of women’s’ roles in society gave way to more progressive attitudes towards female motorists.

After gaining the right to vote in the US with the passage of the 19th amendment in 1919, many women felt for the first time that they were empowered to fight for equality in other areas, and many manufacturers attempted to capitalise on these ideals of self-determination and freedom.

At the time, the newest, most revolutionary and most desirable item on the market was the automobile, and advertising agencies sought to reach out to female consumers using the car as the greatest symbol of female enfranchisement.

Impact of the 19th amendment on industry

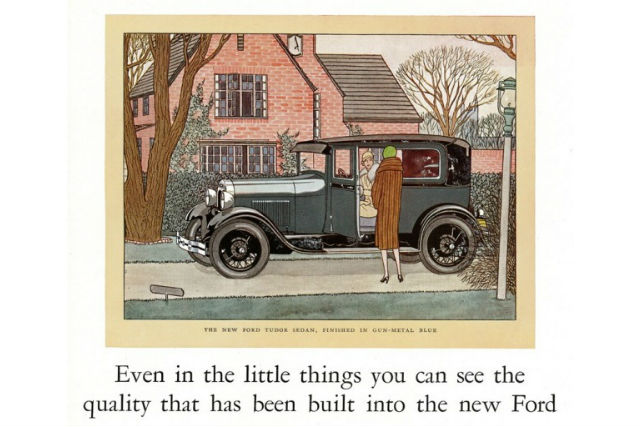

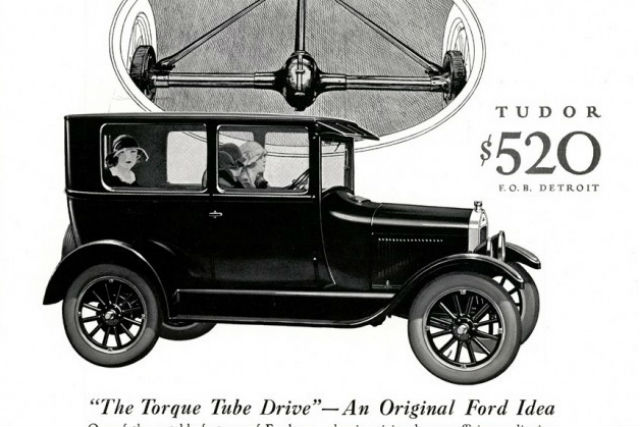

Ford in particular ran a series of advertisements for its Model T, appealing not to accepted domestic behaviour but instead reaching out to women interested in the mechanical assets of the car in a series of campaigns featuring women drivers.

All the same, many of the advertisements of the flapper era reflected the duality of the discourse on women: free to buy cars and travel as they pleased, and yet still bound to traditional feminine stereotypes.

As the 1920s progressed, an increasingly popular theme in automotive advertisements became the ability of the car to allow women to pursue independence on their own without the need for a man or an escort to help them. Although quite obviously relying on preconceived notions of feminine weakness, the overall message in itself was intended to show that the modern woman shouldn’t be prohibited from achieving equality.

Even if it didn’t quite hit the mark, it was of far nobler intention than the advertisements of later decades, which featured women draped across bonnets, looking pretty and reinforcing a heavily-ingrained message that both cars and women were simply men’s spoils.

Those ad campaigns which did attempt to directly reach out to female drivers often tiptoed a line between portraying them as responsible, capable drivers and being utterly condescending.

Misguided to downright offensive

For example, when the Ford Mustang was released in 1964 it became the first sports car marketed specifically towards women. In the same year, Studebaker brought out a driver’s manual which advised any woman who got a flat tyre to: “Put on some fresh lipstick, fluff up your hairdo and look helpless and feminine”.

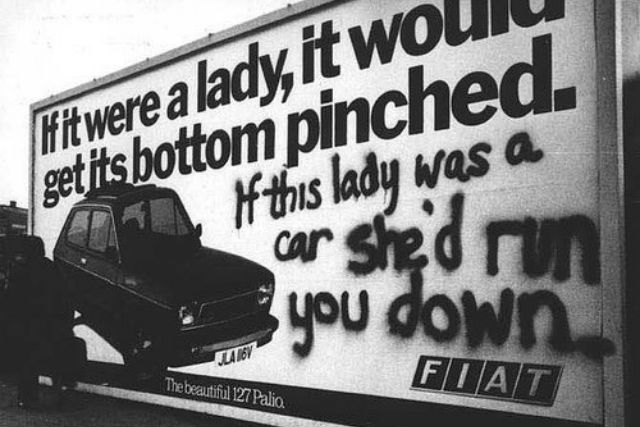

It might seem like something ripped straight from an episode of Mad Men, but attitudes in the automotive industry at that period ranged from the misguided to the downright offensive. Arguably the nadir came in the 1970s and 1980s, when print campaigns were awash with slogans like “If this car was a lady, you’d pinch its bottom”.

For anybody under the impression that those campaigns were just a product of their time or relatively harmless, Margaret Walsh, author of ‘Gender and Automobility: The Pioneering and Early Years’, observed that during the 70s and 80s sexism in the industry had a direct impact on car purchases.

According to Walsh, many manufacturers and dealerships in America at the time not only failed to recognise the tens of millions of working women eager to buy cars, but even went so far as to decline to offer them credit if their husbands weren’t around.

Skip forward three or four decades and thankfully attitudes like these have largely receded from most parts of the Western World, and women are now free to buy and drive any car that they like. Yet, why are they still largely excluded from automotive marketing and advertising?

Performance car market 'no girls allowed'

Aside from perhaps the smallest city cars and hatchbacks, there still aren’t that many cars marketed towards females. The performance car market in particularly in still almost invariably no girls allowed, despite the fact that there are plenty of women who like go-faster cars.

That, and the fact that one of the most supposedly worst insults you can make about a man’s car is that it looks like a girl’s car is a pretty good indicator of where things are at. Decidedly odd, given that women are responsible for an estimate 66 per cent of the decisions to buy more new cars here in the UK.

It’s not even about making marketing specifically for women but, to use Tiffany’s example, to include everyone. If a gay couple can be in an advert for Tiffany jewellery, why can’t a girl be in an advert for a Type-R? Or even a 3 Series?

Perhaps the best thing to engender equality across the industry would be to create diversity throughout companies that matches the consumer base. If an industry wants to reach a wider and more diverse consumer demographic, then it needs to recruit from a far more diverse pool.

Maybe that will mean watering down long-established brand images, and for some that will be much more uncomfortable than others, but already there are signs that the automotive industry is slowly starting to get this.

Take, for example, Mary Barra, who in a decade in which women in Europe occupied less than a quarter of jobs in the automotive industry, became the CEO of General Motors, one of the largest car conglomerates in the world, and thereby the first woman to run a major car company.

Are things starting to change for the better?

Worried about the effect of a female-directed board? Worry not. For the record, General Motors is also responsible for some of the wildest automotive achievements and products like the Hemi V8 engine and still manufacturers a whole slew of testosterone-fuelled vehicles like the Dodge Challenger SRT Hellcat.

Likewise, Aston Martin CEO Andy Palmer created an all-female advisory board to assist with the development of the DBX crossover concept, marking a refreshingly balanced move from the brand that will forever be associated with womanising superspy James Bond.

All the same, type ‘Aston Martin women’ or ‘Dodge Challenger women’ into Google and you’ll get thousands upon thousands of pictures of models draped over bonnets, and relatively little that actually appeals to real women, petrolheads or not.

The automotive industry has made some radical changes in the past few years, taking everything from changing consumer tastes to hybridisation in its stride, and yet appealing to the myriad diversities of the market seems to be its final frontier.

Maybe it doesn’t seem that way on the surface, but there’s a lot that can be learned from a company like Tiffany. The automotive industry, while it’s making slow progress, needs a radical re-tune to keep up with the modern world. Time for those in the driving seat to realise that the modern car buyer is every bit a hybrid as the cars they can buy.