If you’re not from the US or any other country which supports it, jaywalking – the idea of being fined for crossing the road in the wrong place – seems like a bemusing concept.

For anybody from the US, however, it’s a bit more of a problem, with many claiming that it’s a law which criminalises anybody who doesn’t drive a car, and pedestrians caught jaywalking facing immediate fines of up to hundreds of dollars.

Anybody who resists the ticket, goes to trial and gets convicted can be punished with a maximum of $1,000 fine and six months in jail, on top of court costs.

Yet enforcement of anti-jaywalking laws in the US is sporadic at best, often triggered by repeated complaints from drivers in a particular place, or as a result of pedestrian deaths.

Late last year, Los Angeles police started a mass effort to enforce jaywalking rules, with officials claiming that pedestrians were “impeding traffic and causing too many accidents and deaths”, with fines ranging from £115 to £152 for a single offence.

Soon after, officials in New York responded to a spate of pedestrian deaths by issuing a flurry of jaywalking tickets, though the campaign swiftly hit a wall then an 84-year old Chinese immigrant who had been stopped for jaywalking suffered a head injury during a scuffle with police.

Earlier this month alone, a 52-year old man was crossing a street in Halifax, Nova Scotia, when he was hit by a car. As well as suffering two broken ribs and a collapsed right lung, police also gave him a $410 fine for “moving into the path of a vehicle when impractical to stop”.

Regardless of the erratic implementation, jaywalking remains illegal across the United States, and has been ever since the mid-1910s. According to Peter Norton, a history professor at the University of Virginia, the first known reference to jaywalking dates back to December 1913.

A department store in Syracuse, New York, had hired a Santa Claus lookalike who stood on the street outside the store with a megaphone, shouting at pedestrians who didn’t cross properly and calling them jaywalkers.

“I don't know how this got to Syracuse, but in mid-western slang a jay was a person from the country who was an empty-headed chatterbox, like a bluejay,” Norton says.

Initially used to describe folk raised in the country and who were so dazzled by the big city that they couldn’t help but stop and get in the way of other pedestrians, it truly took off as a term of ridicule during the 1920s when automobiles were finally beginning to become commonplace.

According to the historian, a key moment in the legislation’s history came when a petition was launched in 1923 to limit the speed of cars to 25mph. The petition, which had some 42,000 signatures, ultimately failed, but alarmed the US automotive industry enough to try to focus the blame for pedestrian casualties on the pedestrians themselves.

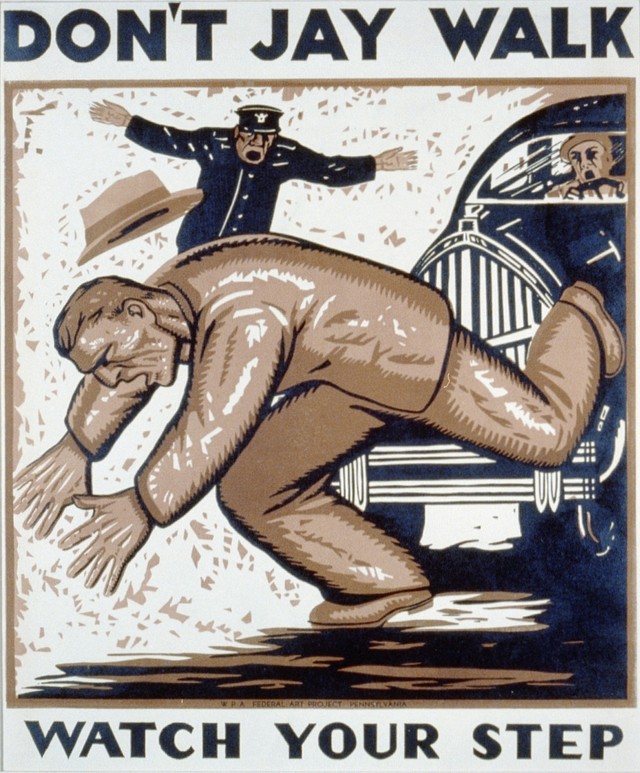

Local car firms hired boy scouts to hand out flyers explaining jaywalking, highlighting that it was supposedly dangerous, old fashioned and unacceptable behaviour for a civilised society. Clowns were also commonly used to portray jaywalkers as ignorant, while local newspapers were provided with reports from the auto industry full of facts about traffic accidents in the area.

“The newspaper coverage quite suddenly changes, so that in 1923 they're all blaming the drivers, and by late 1924 they're all blaming jaywalking,” Norton says.

As a result, anti-jaywalking laws were adopted in many cities throughout the late 1920s, becoming the norm by the 1930s and fuelled by America’s growing love affairwith the automobile. Advertising at the time portrayed the car as the ultimate symbol of personal freedom and the American Dream, with pedestrians little more than a hindrance.

In tandem, city planners and engineers at the time focused on getting as much traffic as possible to circulate within city limits, with pedestrians “essentially written out of the equation”, according to Tom Vanderbilt, author of Traffic – Why We Drive the Way We Do.

“They didn't even appear in early computer models, and when they did, it was largely for their role as 'impedance' - blocking vehicle traffic,” he said. US cities became unusually hostile towards walkers, with jaywalking becoming an oft-misunderstood umbrella term which covered many situations, even some in which pedestrians should legally otherwise have right of way.

Some countries followed the lead of the US, with China, Canada, the Phillippines, Australia and Germany all having rules against jaywalking. Conversely, in some countries like Egypt, a lack of rules or enforcement of any kind means that the only way for pedestrians to cross at all is to launch themselves into oncoming traffic.

In the UK, jaywalking is not an offence, and yet the rate of pedestrian deaths is half that of the US: 0.736 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2011 compared to 1.422 per 100,000 in America.

Public sentiment seems to suggest that anti-jaywalking campaigns are anything but effective, either. When the LAPD advertised its campaign on its Facebook page, it was met with several responses accusing the police of simply seeking easy sources of revenue by fining pedestrians and wasting their time.

“I love how I see people getting jaywalking tickets every day at the corner of 5th and Broadway by our loft, and yet I can't walk to my car without getting offered… any variety of hardcore narcotics,” one woman wrote.

Likewise, pedestrian advocates claim that drivers are most often the ones to blame for pedestrian deaths and injuries, with no evidence to prove that anti-jaywalking campaigns are effective in the slightest.

According to John Moffat, a former commander of Seattle’s traffic police, some 500,000 jaywalking tickets had been issued in the city between the 1930s and 1980s alone. Under his leadership, a change of policy was implemented in 1988 after a study showed that the most vulnerable pedestrians were children, the elderly and drunks, rather than jaywalkers.

Perhaps approaches like Moffat’s show a sliver of hope for pedestrians slapped with jaywalking fines, but then perhaps not. According to Ray Thomas, a lawyer who specialises in pedestrian law, fines in the US for jaywalkers are probably going to continue.

“People in law-enforcement tend to identify with a motorist's perspective,” he says. “It's their version of being fair. The difference is that no jaywalking pedestrian ever ran down and killed a driver, and by sheer survival strategy most pedestrians don't jaywalk in front of cars.”

Regardless, wherever the origins of jaywalking lies, the fact is that it’s now a manifestation of an ongoing and hard-fought battle between vehicles and pedestrians for the use of urban space. There might hope with more cities adopting new planning methods that seek to give equal space to pedestrians, cyclists and motorists, but in the meantime the fight goes on.

Unlike what some suggest, jaywalking mightn’t always end up costing your life. For the foreseeable future though, it might cost you a ticket.