There have been plenty of cars throughout the past 100 years or so that have been unlucky enough to have had the title of “the world’s worst car” bestowed upon them, some have been decidedly more comically misguided than others.

Take the 1899 Horsey Horseless as an example. Created by inventor Uriah Smith, the Horseless was a chuffing early automobile that featured a wooden horse head attached to the front, in order to make it more acceptable to folk used to horse-drawn carriages.

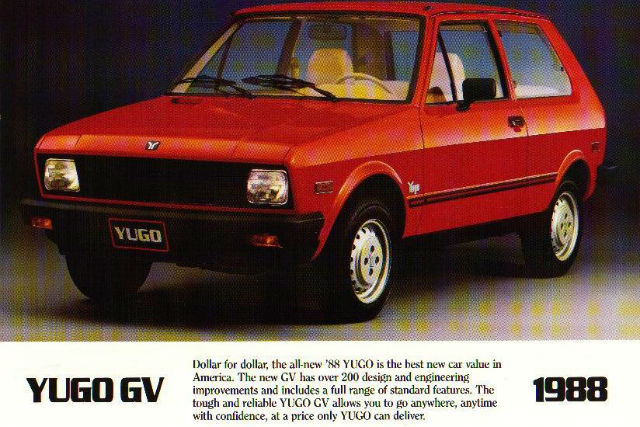

Others, like the DeLorean DMC-12 or Jaguar X-Type weren’t quite as mad in design, but failed to impress with their questionable build quality. Yet, of all the cars ever made, the most loathed, the most derided and the most reviled seems to have been the unfortunate little Yugo GV.

A supermini built for Eastern Europe during the latter stages of Soviet rule, the Yugo started life as a variant of the Fiat 127, manufactured by hand with permission from Fiat. By 1980, the Yugo was mass produced in Serbia and, like the Lada, became a common sight in Eastern Bloc countries.

Lada got its fair share of derision as well, but the Yugo had the distinct feeling of something assembled at gunpoint. The fact that “carpet” was listed as a standard feature said it all really, while the best thing about its rear-window defroster, according to consensus, was that it could keep your hands warm while you pushed it.

This wasn’t the only joke that the lowly Yugo would serve as the butt of as its notoriety grew. What do you call a Yugo with a flat tyre? Totalled. What's included in every Yugo owner's manual? A bus schedule. What do you call a Yugo that breaks down after 100 miles? An overachiever.

Yugo, or rather you don’t.

As if things weren’t bad enough, in 1985 millionaire and founder of Subaru America Malcolm Bricklin began importing the Yugo for an American audience. In its time, it was marketed as one of the cheapest cars in the US, with a sticker price of only $3,995, creating a consumer fad that became known as ‘Yugomania’.

Speaking to TIME magazine back in 2010, author of ‘The Yugo: The Rise and Fall of the Worst Car In History’ Jason Vuic, argued that a large part of the Yugo’s catastrophic reception came as a result of the mystery and hype surrounding its arrival on American shores.

“The summer before it came, you had all this media attention: a $3,995 car? What's going to happen? It's a communist car - will Americans buy it? The press was just nonstop, and it created a consumer fad,” he said.

“Then there's that segment of American car buyers who truly do want an appliance. They don't want their cars to be status symbols; they just want to drive from point A to point B. And there's always going to be a slice of Americans who want a bargain. So in the fall of 1985, people flocked to buy them.”

Rise and fall of 'Yugomania'

As a result, Vuic argued, the Yugo was in part a victim of its own success. Had it not been so hyped up, it probably would have been swept under the carpet pretty swiftly. Instead, once the first customers who lined up to buy the car found out how uniquely terrible it was, the same press that created the hype now jumped on the bandwagon to ridicule it.

So was the Yugo simply derided for the sake of it, or crucified by an American press which was still unwaveringly suspicious of anything that came out of the USSR? Well, perhaps not. According to the testimony of several owners, the Yugo was entirely deserving of its reputation.

Most made it to only around 20,000 miles or so, during which time they would often burn through two or three new clutches. The radio lasted maybe a month, while the gear shifter was notorious for simply coming off.

Dash lights? They burned out near instantly, while rainwater would leak through gaps in the body panels and around the window seals. Even with careful attention and maintenance, power from its 0.9-litre engine was so weak that carrying four passengers was near impossible, while the ignition switch was prone to simply popping out of the steering column.

Worst of all, the design of the car’s engine itself left it prone to self-destruction. A four-stroke interference engine, failure of the motor’s timing belt would disrupt the synchronisation between the engine’s pistons and valves, causing them to collide and potentially destroy the engine.

As one owner wrote: “It made a person nervous to be in it. I recall taking my family to church in it, when it was brand new; they refused to ride in it ever again. You couldn’t trust anything on it and nothing was reliable. I’ve never been able to trust cars again. It was embarrassing to own one.”

Perhaps the Yugo’s darkest moment came in 1989, when 31-year old Leslie Ann Pluhar died when her Yugo tipped over the Mackinac Bridge in Michigan during 50 mph winds. The incident was widely publicised, and despite a legal investigation on behalf of the victim’s family finding that the wind caused the driver to lose control, many blamed the Yugo itself for the incident.

Yet for all of its shortcomings, it’s hard not to start feeling bad for the Yugo, particularly when it was blasted by various press outlets as “a hopelessly degenerate hunk of trash”, a “vile little car” and, most scathing of all, “hard to view on a full stomach”.

“I'm trying to examine why Americans have made it such an icon for failure,” Vuic said. “I wanted to understand why we hate this car so much, even though most Americans have never seen a Yugo, let alone driven one.”

An icon for failure

Indeed, in spite of the Yugo’s incredible reputation for terrible quality, the fact that it was marketed in the United States to begin with meant that it did have to pass certain presale standards. For example, before being able to be sold, it would have had to have passed safety tests, crash tests and an emissions test.

There were plenty of other similarly rubbish cars on offer as well, like the Lada Riva, a Russian copy of a 1960s Fiat that featured technology from the 1950s, the handling of a horse-drawn plough and all the comfort of a gulag.

Like the Yugo, the Riva also fell victim to its fair share of punchlines, like the following classic: Man walks into a service garage. Asks the mechanic, “Can I get a windshield wiper for my Lada?” The mechanic ponders the question for a moment, and replies, “OK, seems like a fair trade to me”.

According to Vuic, these jokes aren’t just restricted to the Yugo or to any Lada car. “They're everywhere,” he said. “There's something about cars that we love to goof on. People love driving high-status cars and love goofing on low-status cars. It shows you the centrality of the automobile in our culture. It is a powerful, powerful object.”

Had things gone differently and the quality of the cars had improved, perhaps things might have gone differently for Yugo. After all, Bricklin’s once-infamous Subarus went on to become an automotive juggernaut in the US, beloved by millions of enthusiasts and daily drivers alike.

Unfortunately it didn’t, and despite thousands of the models still being on the roads in Eastern Europe, the menial little Yugo’s only real lasting contribution has been reduced to a handful of - admittedly quite funny - punchlines.